Weeks before he died, he wrote that, when approach-ing heaven’s gate, “Leave your dog outside. Heaven goes by favour. If it went by merit, you would stay out and your dog would go in.” Mark Twain

I came back after burning the dead body of my wife. It sounds so much better when you can say “I buried my wife.” No, the only improvement would be if I said “I have just returned from my wife’s cremation.”

She died at 12.30 A.M., and a doctor who lived next door and often dropped in for a drink wrote the death certificate because my son who lived with us and is a doctor could not, as doctors can’t declare a relative dead legally. Forgive me; I am chattering nervously.

Yes, my wife had a weak heart, but we hadn’t expected her to die so suddenly. Actually, what happened was that her dog, Moti, ran out because it was mating time, and a stray bitch was wandering around our garden beckoning him. So, at night, Moti jumped out of a window and chased her. My wife became very agitated and rushed here and there. It began raining, so she got wet and had to go a long way before a wet, sulking Moti was found. I went, armed with an umbrella and Moti’s leash. He allowed us to put on his leash and pull him back home. He drank a lot of water, and my wife rubbed him dry.

I said, “First, dry yourself.” Later on, I thought about how this was almost the classic example of a heart attack situation: A fat man on a cold night looking for his dog who has run uphill. Overweight, anxiety, stress, cold, uphill…

Anyway, she was breathless and went to bed. Her heart gave up on her and, before I realized it, she had a massive heart attack and died while I was watching the news on TV in the study. By the time I came into our bedroom, she was no more.

By 4 P.M., we took her to the shmashaan—the cremation ground—after her sister and other women washed her and draped her body in a red cloth that they had bought. I noticed her big toes were tied together with a string and her forehead had a fresh red tilak. She was placed on a bamboo frame, and her still body was soon covered with flowers and garlands.

Neighbours, colleagues and friends milled around, hugging me and pressing my arm, saying sympathetic words. A priest ap-peared and began curating this last journey.

The hearse arrived, and we all accompanied her in cars to the cremation ground, sombre and, like me, surprised. She was so full of life, her sarcasm biting yet witty, so ready to have fun, so focused on her job as a copywriter in an ad agency, selling every-thing from soft drinks and chocolates to lignite with great enthusiasm.

At the destination she was placed on a pyre made of wood and covered with logs, her feet facing south. The priest came after a hurried bath and began telling me what to do.

I looked at Rajat, our only child, and he seemed stunned. His eyes flowed with tears that he kept wiping with his hand, and sometimes with the end of the new white dhotis—one around his waist and another around his upper body—just like me.

I went around the body, which lay on the logs while the priest chanted hymns. Guided by the priest, I sprinkled ghee, sesame seeds and rice—well, the priest actually sprinkled her mouth with the ghee and rice. He drew three lines and told me they signi-fied Yamaraj, the god of death. I walked around the body, holding a pot of water on my shoulder. It had a hole, through which the water trickled out. I threw it near her head, and it shattered without much noise.

I heard sobs and moans from the mourners, but I neither sobbed nor cried. I just kept staring at the body, and almost ran away when I was given a piece of burning wood to set the body on fire.

The priest chanted and told me,

“Now the fire cannot touch her.

Burn her not up, nor quite consume her,

Agni: let not her body or her skin be scattered.

O all-possessing

Fire, when thou hast matured her,

Then send her on her way unto the Fathers.

When thou hast made her ready, all-possessing Fire,

Then do thou give her over to the Fathers.

When she attains unto the life that awaits her,

She shall become subject to the will of gods.

The Sun receives thine eye,

the Wind, thy Prana (life-principle, breathe);

Go, as thy merit is, to earth or heaven.

Go, if it be thy lot, unto the waters;

Go, make thine home in plants with all thy members. — Rigveda 10.16

Some of the male mourners were pouring ghee over the logs and, when I touched the burning log to the pyre, it burst into flames as she lay there. The priest and my son did the Kapala kriya, thrusting a sharpened bamboo shoot at her skull to crush it and release her spirits. The fire blazed. The air filled with a light smoke and cinders. I turned away as her body burned, the red cloth turning black and curling into ash.

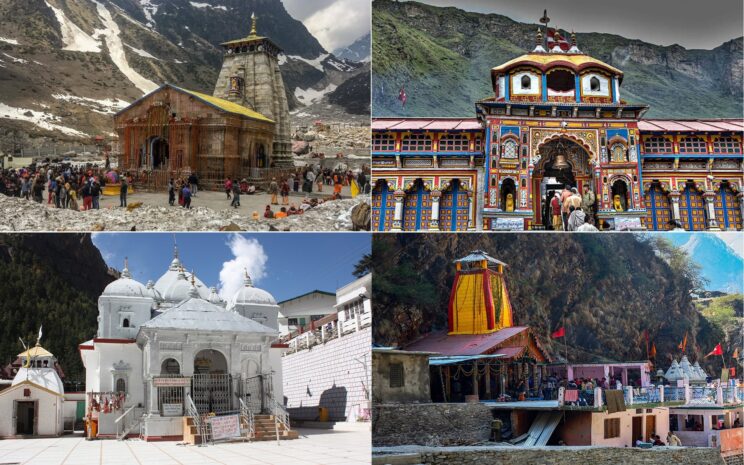

The priest told us to have a bath as soon as we got home and to return tomorrow to collect the ashes and some bones from the cold pyre. We have to take it all to Haridwar or Varanasi and immerse it in the Ganga before taking the pot with the ashes home. If we wanted, we could shave our heads, especially Rajat.

So I came home and showered. When I came out of the bathroom, like a shock, I heard the whimpers of her dog. When I went towards him, he slunk away.

“Ramuji!” I called the cook, who rushed into the room. “Did you feed Moti?”

Ramuji nodded yes and said, “That I would not forget, saab, not when she has gone. She loved that dog too much, saab.”

Moti is a two-year-old golden retriever, light brown with a black mouth and nose and amazingly beautiful dark-brown eyes. His coat falls in streaks of every shade of brown around him. His bushy tail is always alive. In every way, he looks like a dog who was loved obsessively, until yesterday.

The dog slept on her side of the bed, as always, and I lay on my side and watched the news on TV. He curled up in his huge, round bed, sometimes looking at me dolefully, sometimes getting up to circle the bed. At last, he walked to the door that led to the garden and barked softly until I let him out. I stood in the garden and seemed to hear her endearments for the dog as he ran around, so playful and happy. Today, he walked down along the wall and came back to the door. I patted him, and he looked at me with eyes that said so much.

I watched him slowly walk all around, sniffing at chairs, cupboards, doors, and the easy chair she usually sat in.

Ramuji told me next morning that Moti hadn’t eaten his breakfast and, wiping a tear, he added, “He is not like himself at all. I don’t know how to tell him what has happened.” I didn’t know either.

I tried to coax him into eating the egg and paratha, but he turned his face away. I got a ball and tried to play with him like my wife would, but he curled up and looked either sleepy or sad. I found his jerkey and treats and offered them to him, but he licked them once and refused to grab any of it with his mouth as I had seen him do when she would give them to him.

My son came out and told me we had to pick up her ashes. Moti leapt at the car door until I let him in, despite my son’s irrita-tion.

“How can you take him to the shmashaan, Papa? Please don’t let a dog make you think he knows. He will be all right. Hey, Mo-ti, come on, go inside.” He tried to push him back into the house, with no luck. I opened the back door to let him in, and we drove to the cremation ground.

Moti sat inside the car and, while we picked at the ashes for bones or teeth and a worker filled a pot with the ashes, Moti sat on the side and cocked his head from one side to the other in an almost comical way. I tried to remember how my wife talked to the dog and, floating in my memories, she seemed to tell me, “My dear, dear doggie doggie, come to Mamma and let me kiss you. Moti, my pearl, my precious Mitti, Motu, Moti baba, Moti baba, where have you been?”

We got into the car holding with her ashes. Rajat almost laughed as I patted Moti and murmured, “Mitti, Motu, Moti baba, where have you been?”

We left for Hardwar a few hours later with Moti in the backseat. Another car came with us, bringing her sister, her brother-in-law, and her uncle. Everybody protested about Moti, but there was laughter too, surprising me as we were still stunned and sad. Only Moti seemed doleful: he wagged his tail and licked my hand and stared at the front door, willing his mamma to come out.

In Hardwar, Moti ate puris and aloo. He drank water from his bowl, which we had carried with us, and Rajat took him behind the shops to relieve himself. I took him on a leash to the river. He sat on the steps and shot disdainful looks at a few stray dogs who barked incessantly, eventually getting shooed away. The priest we had hired smiled at Moti, and I asked him if it was all right.

The priest asked, “Was he the deceased’s pet?”

“Yes, and inconsolable,” I said, patting Moti on the head.

“Usually, I would not allow it, but the dog seems well trained, and even I can see he is disturbed. They know. You know, a dog followed the Pandavas to heaven’s door, climbing up the mountain. Even when only Yudhishtir survived, the dog followed him, and when Indra came to escort him to heaven, he refused to leave without the dog.

The dog was actually Dharma.”

“Thank you so much, Punditji,” I said softly.

Moti sat quietly near us and watched the ashes float away with the flowers, craning his neck as they floated further away. All of us smiled seeing his posture and patience. Most of the others, including my son, discreetly took pictures of Moti on their phones.

On the way back, Moti had puris and aloo with us again at a shop on the highway. He barked at a man who had dressed—and even painted himself—like Hanuman, but Moti stayed leashed and close to me. We drove back, entering Delhi almost by mid-night. Moti was asleep on the back seat. When we reached home, my son parked the car, and I let Moti out. He jumped down but waited.

“Mitti, Moti, Mutoo, come on.” I stared in disbelief, because the one saying that was my son, in a falsetto imitating his moth-er. Moti jumped at him, and we both cuddled with the dog. At last, I cried. I sobbed so hard that my son had to drag me back into the house, firmly but gently, with Moti barking and jumping all over us.